Horse people talk to each other. They talk to each other a lot. Right now that means keeping proper social distancing, and communicating virtually as much as possible. But the conversation continues.

The other day some of us were talking about bad horse habits, and by extension, bad habits of humans writing about horses. Every horse buyer has a list of nonnegotiables, some of which end up being negotiated anyway. “There is no way I will ever buy a chestnut Thoroughbred mare,” declares the buyer who, in the way of fate and the world, finds herself signing a sale contract for a young mare straight off the track, whose coat is as bright as a copper penny. Often that works out wonderfully, and the buyer grudgingly admits that Chestnut Mare Beware is a mere and invidious stereotype.

There are some things however that really do make or break a sale, and less than honest sellers will take measures to conceal them from the buyer. Unlike the bias against equine redheads, the trope of the slippery horse dealer is a little too accurate, a little too often. They’re the used-car salesmen of the horse world.

While color, breed, looks, gender, and to a large extent size may end up not mattering if horse and human click, behavioral and training issues are huge. An experienced horse person may be able to handle a fairly broad range of problems that would (or should) be a fast Nope for the less experienced, but there will still be a list of things that the buyer (or trainer) is not willing to deal with.

My personal No Way list includes bucking, spookbolting, and one I will be coming back to: rearing.

Bucking is a familiar sight for the film and television viewer. There’s the standard scene with the cowboy breaking the bronc, throwing a saddle on and riding out the bucks till the horse gives in, or as often as not, getting bucked off. This produces various plot bunnies including the mockery of the railbirds watching the show, some form of injury to the rider’s body or pride, and eventually, maybe, the successful domination of the wild horse.

Bronc-breaking has been and in a few places still is an acknowledged way of getting horses under saddle, but it’s the literal quick-and-dirty method, and it’s brutal for both the horse and the human. Responsible trainers these days take more time, as in weeks or months, and do it gently, persuading rather than forcing the horse to accept saddle, bridle, and rider. Instead of breaking the horse’s mind and spirit, they win it over. And, if it’s done right, the horse is a willing partner and it keeps its fire and spirit.

However. Even a properly trained horse may for whatever reason be prone to buck. That may be how that particular horse happens to register objections. It may resort to bucking when confused or startled. Maybe the saddle doesn’t fit properly, is pinching or rubbing. Maybe there’s something awry in the back or neck, and the pain makes the horse upset, and it bucks. Maybe the bit is too harsh, or too small, or too busy for that particular horse. So he grabs it and gets his head down between his knees and humps his back and off he goes.

I hate that. Even though my favorite riding horse of all time has a buck in him like a rodeo bronc (yes, there are whole lines of horses bred specifically for that event, and they are good at it and they love their job), he only does it if his saddle isn’t in exactly the right place and his back isn’t warmed up exactly the way he likes it, so that’s on me. But if I were buying a horse (versus raising the one whom I bred), I would cross him off my list.

Likewise the very spooky horse, the one who levitates sideways, and the one who takes off like a shot, brain locked in Off position, completely impervious to anything the rider may be doing. Spookbolters are bloody dangerous, not just because they can shed the rider and damage her badly, but because they don’t care what happens to themselves, either. Their only thought in the world is RUNRUNRUN, and they will run off a cliff or into a tree or straight into an oncoming truck. That is bad. Bad, bad. Give me a horse with a brain that stays in gear, and that cares whether I’m alive or dead.

And that’s about safety and good horse sense, but there’s one more bad habit that has become a trope all its own. I blame Hollywood, and I blame it hard.

That vice is rearing. A horse that rears, that is light in front, that goes up when you want him to go forward, is freaking bloody dangerous. It’s not just that you can’t get him to go. It’s that if you push, you’re all too likely to drive him farther up, and then he’s all too likely to crash over backwards. That can kill you, and it can break him.

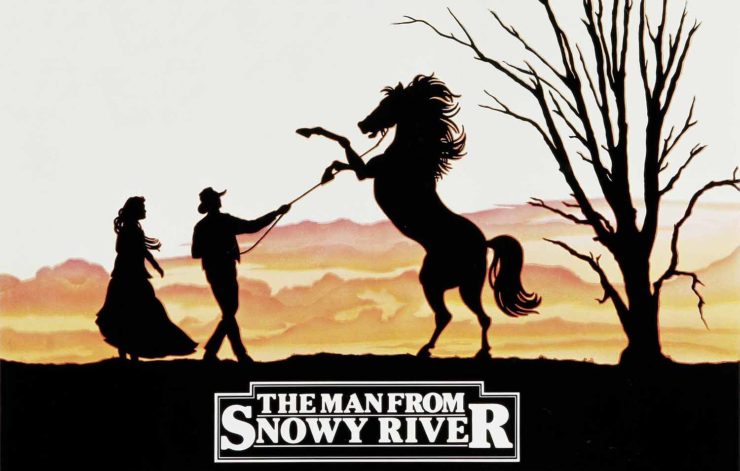

The problem isn’t just that a rearing horse is a danger to ride. It’s that he’s a freaking Hollywood meme. Every single damned horse in every single damned horse movie, bad or good, rears. He’s on the poster for one of the great horse movies, The Man from Snowy River. He’s in every single romance movie in which the hero comes riding out on his fancy-ass horse, and stops. And rears. Hi-yo Silver! Yay, Trigger! Hello, generic movie horse showing off for the crowd!

Obviously somebody, at some point, decided that a horse on his hindlegs makes good movie-foo. He’s literally ten feet tall when he does it, and you can have fun with camera angles. It’s easy to train, and it looks impressive. People who know zip about horses and riding go all, Whoa and Wow and Heeeyyyy.

The trouble is, the meme perpetuates itself. If one movie horse does it, they all have to do it. And then you get people who don’t know any better, including writers who are trying to write about horses in their novels, thinking that this is [a] cool and [b] legit.

What it is, for actual horses and actual riding, a serious vice. Anything dangerous that you train a horse to do will pretty much inevitably become the horse’s go-to. If it starts as an evasion, he’ll find that it works, and past a certain point he won’t be correctable. If he’s actually trained to do it, he will do it All The Time. There won’t be much else he wants to do, and he won’t be much use for anything else.

And that, young writers and riders, is why rearing is not a cool thing to have your horse do. If your horse is rearing, in real life or in your writing, he’s demonstrating that you have not trained him or yourself correctly.

And yes, I do know a fair bit about the high-school, highly trained, very noble Air called the levade, which is the pose favored for equestrian portraits, especially in the Baroque era. That’s a lot less dangerous than the Hollywood rear, in that the horse’s hindquarters are much more under him and the angle is lower (30 degrees or less), and it takes tremendous strength for the horse to do it at all. But even that comes with a warning from the trainers of the haute ecole, which is that once you’ve trained an Air, that’s all the horse wants to do. Best leave it to a specialist and refrain from teaching it to the horse you want to keep as an all-around riding horse.

In any case, for those who really do know about horses, the most impressive performance of all is the quiet, cooperative, consistent one. No rearing, bucking, fussing, or fighting. The quiet rider on the quiet horse is the real hero, the one who will get the job done and win the day.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has even written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.

Hear hear. Not “Rear! Rear!”

Also, those of us who only know movie horses really have no concept of what horses can and can’t do, will and won’t do. I got tickets sort of accidentally to see a touring show of the Lippizaner horses years ago. I went, but… aside from the really really fancy stuff, I didn’t know what I was looking at. Luckily the woman sitting next to me would gasp or break into applause, giving me some kind of a hint. I had no idea that it was difficult to teach a horse to trot in place or canter in a circle. To the uneducated, it’s a hard thing to appreciate.

Thoroughbred Chestnut Mare. I’ve said it, now I lease it.

Oh Karma, thou art a heartless bitch.

What’s up with horses in movies talking all the time? No, not Mister Ed talking. I mean horse talk — whinny, neigh, nicker, etc. Real horses typically aren’t chatterboxes. Unless they’re upset.

I’ve read that rearing with a rider is dangerous primarily because of balance and the possibility of going backwards or sideways. Fortunately, I never had to deal with it.

If the horse fairy visited me and made all the reasons I can’t have a horse anymore go away, I’d say the number one thing I wouldn’t want in a horse is stupidity. Lady was scary smart, but my friends’ horses were, by and large, stupid, and a horse we boarded had less brains than a potato. My brother had to take apart part of the stable because that idiot managed to get itself trapped in a walkway between stalls after her owner left a door open. I’m not a fan of stupid in any species.

I used to ride a rear-er, and would lean forward to keep my weight centered. So one day I did that and my head ran into the horse’s. Stopped riding that horse.

Never was on a horse that reared or bucked. Been on some that didn’t want to be ridden and had various ways of making that clear, and once (when I was 7? 8 maybe?) a pony who decided that today was a day to RUN! FAST! FOR FUN! Scared hell out of the person running the stable when the pony just took off with the little kid on the back holding on for dear life and laughing.

Dagnabit, what is this bizarre prejudice against gingers bipedal & quadruped? Shouldn’t Man O’ War and Secretariat be a splendid argument against such colour prejudice? (Well, maybe not the former, that one had a redhead temper to go with the ginger coat).

Is this a Homo sapiens V neanderthal thing? It’s been several ages people, aren’t we all a little neanderthal?

On a more serious note, rearing is definitely one of those impressive looking displays that one wouldn’t want to be sitting on top of … or, for that matter, standing right in front of.

I kind of realized that movie horse behavior wasn’t normal about the same time I realized how many behaviors of animal X in movies weren’t normal. I’m also pretty sure that jumping from a second-story (US terminology) window onto the back of a horse would result in some undesired side effects, like the horse bucking or rearing to get that damned predator off its back or collapsing in pain because of having a 180-lb human drop onto it at about 25 ft/sec (about 17 mph).

On the other hand, some of the behavior trained for in equestrian high school is a bit weird. Yes, there are quadrupeds that pronk (which looks a lot like the croupade) and hop, but training a 1,000 lb horse to spring about like a 100 lb gazelle or hop like a 10 lb rabbit (courbette) seems a bit outré

Outre but lovely to see

@9 They do it on their own. I have had two mares who defaulted to courbette (standing straight up and hopping). One was Very Large, and when she went UP, it looked like a mountain dancing.

One of the things the major Lipizzaner studs like to do (including Tempel near Chicago) is bring out the babies and let them run in the exhibition arena during their shows. They never fail to demonstrate the Airs. The fillies have particularly strong antigravity generators.

@@.-@ When I was in college, my room mate and I were watching a Western series on TV. Yes, this was ancient times. A scene where the barn catches on fire and all the horses were screaming came on, and I started laughing. My friend was shocked because I loved horses and stated more than once that a barn fire is a horseperson’s worst nightmare. I explained that the horses weren’t terrified. They were annoyed about breakfast being late. The horse version of “Feed me! FEED ME NOW!”

@6 Martingales. Not my favorite thing, but it stopped my nose coming in contact with my mare’s hard head.

@8 23 & Me includes info on whether you have Neaderthal DNA so, apparently, a lot of people do.

@11,

Wow! For adult horses, this surprises me greatly; I would think that this would hurt and would be dangerous as natural behavior. For fillies, I’m not to surprised, because fillies are equine children and even human children can do all sorts of things their parents can’t or won’t because of pain or fear of pain.

@11 They’re genetically engineered for it. Strong, dense bone, feet like iron, and powerful musculature with tremendous stamina. They can do things that most horses of their size and weight cannot do. The stallions of Vienna are carefully and meticulously trained, but the training builds on what’s there already. Nothing they do is unnatural. The hard part, once you’ve trained an Air, is to keep the horse from defaulting to it.

I was riding in a clinic once with a Bereiter from Austria, and one of the other riders had a horse who had performed the courbette for years in exhibitions. She was working on other movements, but sure enough, if he decided he didn’t wanna, down would go the butt and up would go the rest of him. It was easier for him than a plain old garden-variety piaffe, and from his expression, quite a bit more fun as well.

I have never trained my horses to do Airs for this reason, but they have freaked out a vet or two when being given shots, by going up in levade. Not a rear; the school Air. It’s built in. And I have had them courbette and capriole for Reasons, and very precisely, too. Their proprioception is…really something.

The proudest moment of my childhood was being bucked off my cousin’s Shetland pony, because I was horse mad and knew I’d never be able to do more than take riding lessons and this made me feel like I’d made it as a tiny horsewoman. Of course it was because Candy was badly trained and had bad habits (and was not into the role of mount), but (since I wasn’t hurt) at the time I thought it was awesome. (She also stepped on my foot solidly enough that I had a hoof-shaped bruise – which (since no bones were brokenn) was also awesome.)

I was a weird kid…